|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

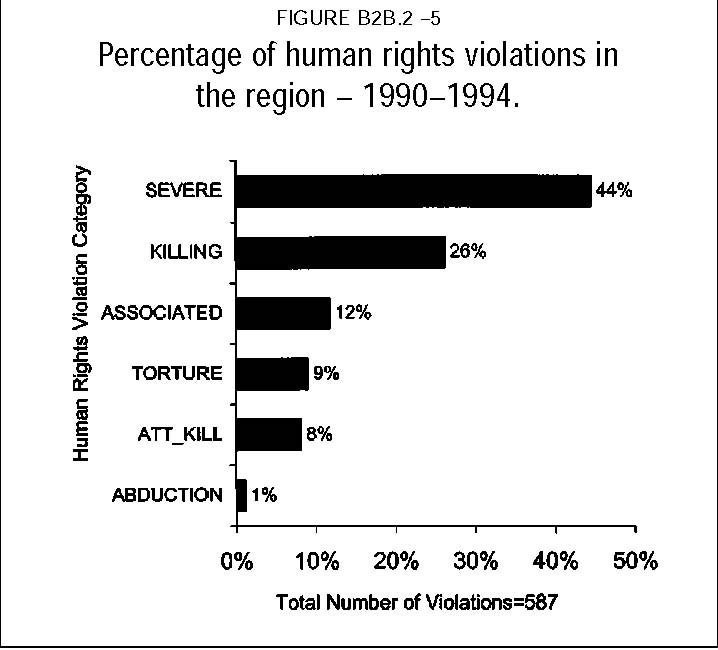

TRC Final ReportPage Number (Original) 486 Paragraph Numbers 323 to 332 Volume 3 Chapter 5 Subsection 50 ■ 1990–1994Overview323 The 1990s saw a fairly extensive upsurge of violations in the region – although not remotely approaching the levels of violence in other regions. An estimate of deaths from newspapers and Commission sources suggests that there were around 200 politically related deaths in the Peninsula alone, although in many instances criminal or taxi elements may have been involved. It is notable that the Peninsula violence was restricted almost exclusively to the African townships, apart from isolated incidents elsewhere, in particular APLA attacks. The rural areas also experienced struggles and conflicts with local authorities and police. There were numerous deaths and injuries in Northern Cape towns, while resistance to ongoing apartheid segregation in the Boland resulted in what became known as the ‘Boland War’. 324 The Peninsula shared the trend towards anonymous violence that emerged across the country in the 1990s, with the emergence of ‘vigilante-type’ anonymous violence that primarily targeted the liberation movement supporters. The proliferation of ‘balaclava’ gangs striking at families or whole communities was a strong feature of the violence from 1991 to 1993. Conflicts with the local town councils as well as inter-organisational conflict, particularly in the Civic movement, played a role in this. 325 The most extreme violence centred in and around informal settlements in Khayelitsha and Crossroads, whose political loyalties were vigorously contested by both the state and the liberation movements. In addition, the tremendous upheavals generated by the piecemeal upgrading and development process caused widespread conflict and fragmentation within these communities. 326 As elsewhere, there was an increasing blurring of the distinction between criminal and political violence. Certain activities of the Peninsula self defence units (SDUs) became criminalised, while taxi-related conflicts became increasingly politicised. 327 The liberation movements themselves were involved in violations at differing levels. Within the ANC, violations centred mainly around internal conflicts and renegade SDUs. The PAC engaged in several military attacks on both civilian and security targets, resulting in many casualties. The Western Cape was one of APLA’s chief fields of operation in the period. 328 In the 1990s, political assassinations feature in the region for the first time, with victims including Ms Nomsa and Mr Michael Mapongwana, Mr Super Nkatazo, Mr Lucas Mbembe and Mr Mziwonke ‘Pro’ Jack. While the assassins had a variety of political affiliations, collectively they matched the pattern elsewhere in the land. In particular, the taxi wars exacted a heavy price upon political leadership. 329 The Commission is of the opinion that it has not been able to obtain a fully representative sample of statements regarding the multiplicity of conflicts in this period. Tensions and conflicts still prevail in certain areas, and the Commission has reason to believe that victims were not encouraged to give statements in some areas, or were even actively discouraged from doing so. In addition, the marginalised nature of informal settlements (where most of the violations took place) would have contributed to a lack of knowledge about and participation in the process of making Commission statements.46 46 With the establishment of a range of human rights-linked NGOs in the western Cape in the 1990s, a great deal of recording and analytical work was done on most of these areas. The Commission cannot reproduce the excellent work of these structures, but has drawn upon it.Overview of violations330 This period contains the second highest number of violations reported in this region. Severe ill treatment remains the most common violation, followed by killings.  Conflict with local authorities331 From 1990, a series of conflicts unfolded in the region in which residents tried to challenge the local power relations and rule by local authorities. These took place in both urban and rural areas, often with fatal consequences. They were sparked largely by the unbanning of organisations and the beginning of negotiation at national level, a process that was not matched at local level. Local communities attempted to challenge both the lack of change in local government, as well as ongoing racist and discriminatory practices. 332 The conflict was felt throughout the western Cape, but was most marked in Khayelitsha and the Boland (see below). |