|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

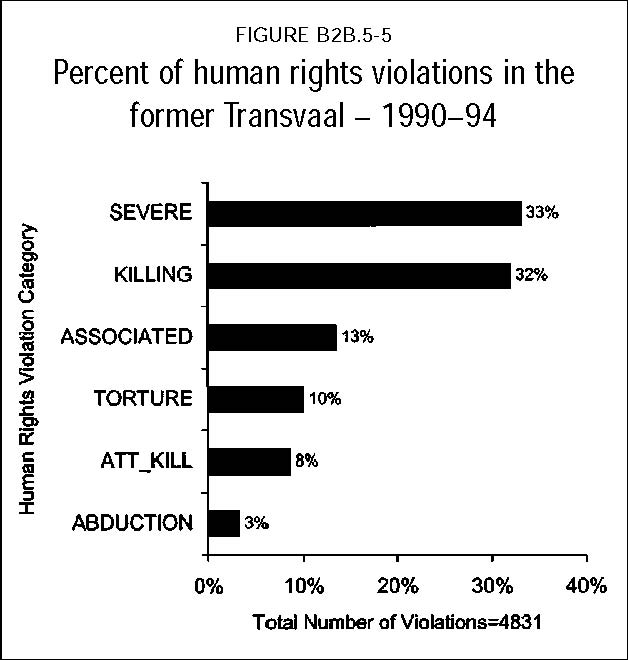

TRC Final ReportPage Number (Original) 670 Paragraph Numbers 526 to 533 Volume 3 Chapter 6 Subsection 72 ■ 1990–1994Overview of violations526 Between 1990 and 1994, political violence claimed the lives of approximately 15 000 people. According to the HRC, during the preceding five years, 1984–1989, 3 500 people had died as a result of political conflict. The SAP estimated that, in 1990, damage to buildings and vehicles as a result of ‘unrest’ led to losses of R105 million compared to R34 million lost the previous year32 . 527 Evidence before the Commission shows almost twice the number of reported killings (circa 1 550) occurred between 1990 and 1994 as in previous period (circa 850), becoming the most frequently reported violation.  528 The contest for power set in motion by the unbanning of organisations and the opening up of political processes in 1990 led to a substantial proportion, although not all, of the violence reported in the Transvaal in the period. The violence took the form of internecine conflict, rather than direct conflict with the security forces as in previous decades. 529 Much of the conflict that took place during this period was concentrated in the PWV (Pretoria–Witwatersrand–Vereeniging triangle) region of the Transvaal. Until July 1990, ongoing internecine violence had remained largely confined to Natal. However, in the wake of an Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) rally at Sebokeng in the Vaal Triangle, which left twenty-seven people dead, it moved rapidly to the Transvaal, spreading to the East Rand, Soweto, the West Rand and Alexandra townships. In each case, non-Zulu hostel-dwellers were driven out of the hostels, which became launching pads for attacks against surrounding communities and, in particular, informal settlements. 530 Ironically, the violence of the 1990s took place in the context of political reform and a process of negotiated transition. However, it was precisely this process that precipitated the rapidly escalating conflict. The unbanning of political organisations by FW de Klerk in 1990 and the possibility of democratic elections created an environment of intensified political competition as long-banned political organisations returned to re-establish themselves in the country, while other organisations such as the IFP entered the national arena as a formal political party. 531 Although the violence was precipitated and fundamentally shaped by the contest for political power which took place in the wake of the unbanning of political organisations, there were a variety of other divisions, including generational, economic, territorial and personal, that impacted on the form that violence took and motivated people’s participation in it. These conflicts were intensified by the context of poverty and disempowerment within which they occurred. 532 The stakes were very high. The open expression of diverse political opinions had long been suppressed and levels of political intolerance were extremely high. In July 1990, COSATU called a stay away to protest against the high levels of violence in KwaZulu-Natal. Allied to this initiative, a number of organisations, most notably the South African Youth Congress (SAYCO), declared Inkatha “an enemy of the people” and the houses of many IFP officials in the Transvaal, particularly those town councillors who had allied themselves to Inkatha, were petrol-bombed.33 On the other hand, members of the IFP were reportedly involved in a forced recruitment campaign in the PWV hostels, were expelling non-Zulu residents from hostels and engaging in numerous acts of violence against township residents and ANC supporters. 533 Evidence before the Commission for the area covered by the Johannesburg office reflects a shift away from the direct conflict between former state and its political opponents that dominated all previous decades. During preceding periods, the most frequently identified perpetrator was consistently the South African Police (SAP), during the 1990s, the number of violations attributed to the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) exceeded those attributed to the SAP. The SAP, however, remained the second most frequently identified perpetrators of reported violations. During this period, members of the ANC were also identified as perpetrators of gross violations. The arming of ANC self-defence units (SDUs) increased levels of violence as these units became involved in local conflicts, sometimes abusing their power. Right-wing organisations during this period also engaged in sometimes violent opposition to the political reforms introduced by state president Mr F W de Klerk. Criminal gangs, such as the Toasters and the Zim Zims, were also drawn into the political conflict, becoming perpetrators of political violence for the first time.34

|