|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

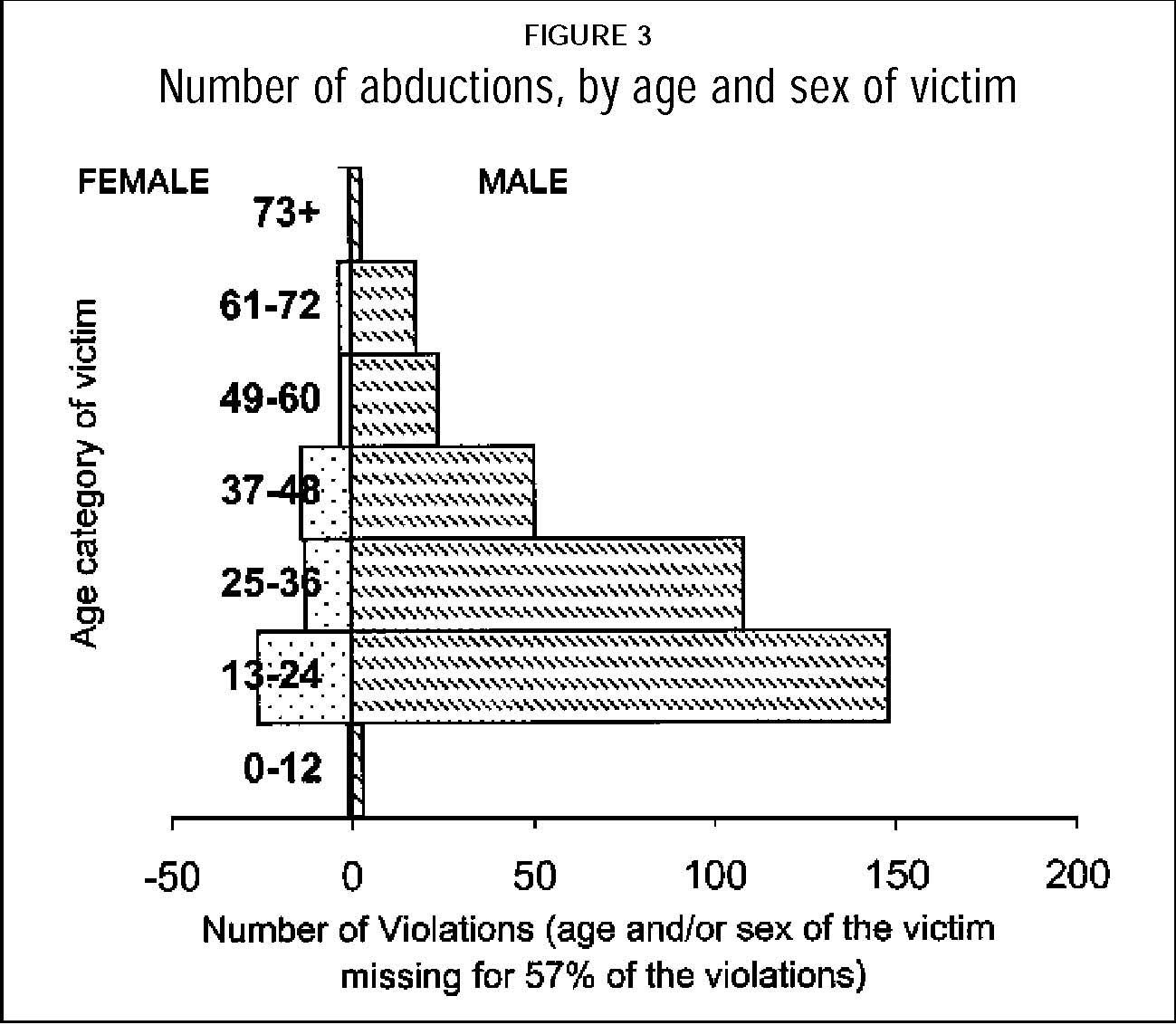

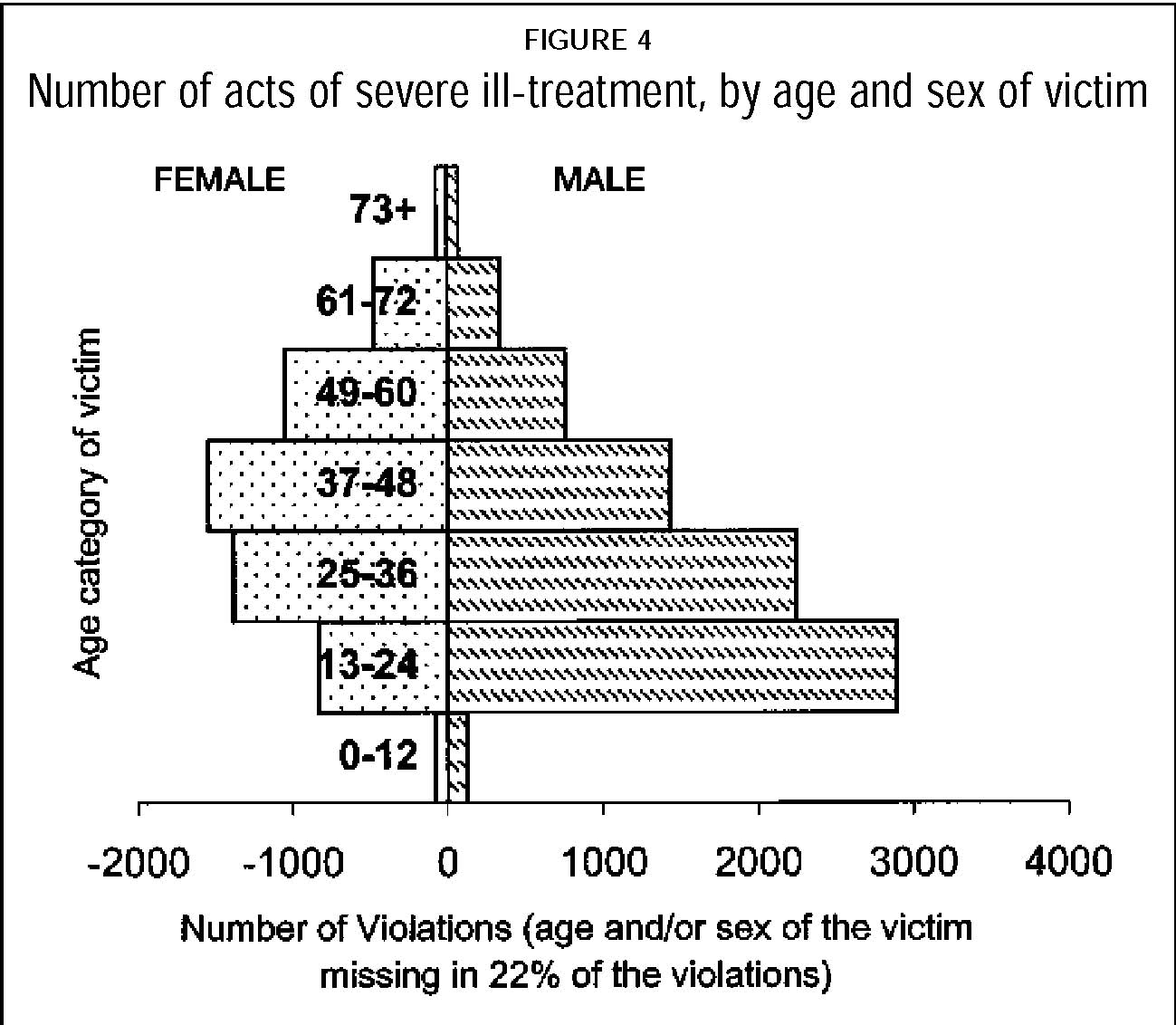

TRC Final ReportPage Number (Original) 266 Paragraph Numbers 71 to 83 Volume 4 Chapter 9 Subsection 9 Intimidation of families71 The childhood of the children of activists was often filled with fear of police intimidation and violence. Ms Nolita Nkomo was born in February 1970. Most of her recollections of her early teenage years are of threats and intimidation, especially when members of the security forces bombed her family home. By the time she was sixteen years old, her house had been bombed three times. Threatening telephone calls were a regular part of home life. The family experienced many sleepless nights – lying awake in a state of tension after being told, repeatedly, that none of them would see the next day dawn. 72 Ms Nomakhwezi Gcina, the daughter of Eastern Cape activist Ms Ivy Gcina, spoke of the difficulties and stresses of growing up as a child in an activist home: I’ve led a very difficult life starting in 1977, when Samora, our eldest, left this world. We’d be sleeping at night and the police would come kicking the doors down, wanting to know where my brother was and beating us up. They would burn our house down, arrest my mother and we would be left without a mother. In 1980, Msimasi left and even [then] they would wake us up in the middle of the night beating us, wanting to know where our brothers were. I think the most difficult time in my life was in 1982 when we also lost my third brother who was in exile and only two of us were left. In 1982, when my brother was eleven years old, both my mother and father were arrested and the two of us were left alone in the house. They were arrested under section 29 and we could not even visit them; even our pastor could not visit them. We were treated like animals, my brother who was eleven years old and myself. Nobody was visiting us and even members of our extended family isolated us. As my parents were still in detention the police came [in the] early hours of the morning (but fortunately there was a lady who came to spend the night with us) and they kicked the doors down as usual. They never knocked; they just kicked the doors down. That was the norm. They asked Mzokolo where our relatives were and he said he did not know; he only knew where our parents and siblings were. He was wearing short pyjamas and they beat him up and took him with [them] in a very harsh manner. We were left behind and didn’t know what to do. He came back the next day at two o’clock. He was swollen and he couldn’t even see. He also passed away. In 1985 up to 1989, giving a summary, my mother was arrested and put in detention for four years but no charges were laid. I lived with my father. Abduction73 The extent to which violations were perpetrated against the young is again revealed in the data on abduction. The majority of those who were abducted were young males between the ages of 13 and 24. In the case of women, young rather than older women experienced this violation.  74 Ms Florence Madodi Nkosi, who testified at the Mmabatho hearings, was a victim both of abduction by vigilantes and of police abuse. On 24 November 1985, after attending a meeting of the ANC Youth League, a group called the Inkathas or A-team, which was working with the police, abducted her. She was taken to a shop in Huhudi. They caught us and they put us into a shop and started assaulting us with sjamboks and knobkieries15. They hit me a lot on my head. Every time I would touch my head, it would be soft. They hit me until I could not feel the pain anymore.15 A sjambok is a whip; a knobkierie is a club. Severe ill treatment75 Young males between the ages of thirteen and twenty-four reported the highest incidence of severe ill treatment of all age categories. Among females, women between thirty-seven and forty-eight years of age were most commonly the victims of severe ill treatment.  Children and youth in exile76 In the face of mounting repression, many young people or their family members left the country to reside in other countries or to join liberation movements. 77 Exile is often experienced as a brutal rupture in an individual’s personal history, resulting in a lack of continuity that frequently becomes a serious obstacle to the development of a meaningful and positive sense of identity. It has been argued that political repression and exile tend to distort normal socialisation in a child or young person. Some of the significant consequences of life in exile include a feeling of ‘transitoriness’, a profound sense of loss of security, feelings of guilt, and a range of more severe psychological problems and disorders. 78 At the Eastern Cape hearings, evidence was presented about the impact of exile on children and young people. Professor Mbulelo Mzamane, founder member of the South African Refugee Committee and himself exiled as a child, testified about the experiences of young people in exile. He identified three key periods during which South Africans were driven into exile: the Sharpville generation, the Soweto generation, and the post-1984 (UDF) generation. 79 Professor Mzamane described the trauma of escape. He recalled the experience of receiving ‘Queenie’, a girl of eight years of age, who had walked over the border under the cover of darkness. On arrival, she was detained by the Botswana authorities as part of the normal procedure for the reception of exiles. 80 Inadequate shelter, hunger and the ever-present threat of kidnapping by the South African state were the daily realities of children in exile in frontline states, including Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland.16 81 One of the leaders of the Soweto uprising of June 16, Tsietsi Mashinini survived no less than three kidnap attempts whilst living in Gaberone in Botswana until it was felt necessary that he should leave Botswana to go where it would not be possible to have him kidnapped. He eventually fled to Liberia where he subsequently died. 82 The exodus resulted in the breakdown of family units and the severing of links with extended families, with traumatic effects on the lives of many young people. Exiled children often grew up without their parents or primary care givers. They were unable to contact family and friends in South Africa because of the risk of reprisals against their loved ones in South Africa. The conditions to which they were subjected included exposure to disease and hunger. Some were unable to hold onto clearly defined identities, partly because of the ruptures between them, their kin and their homeland. 83 It is not clear how many young people and members of their families died in exile, either as combatant members of the liberation movements, or because of natural or other causes. Some died as a result of cross-border raids into neighbouring countries. 16 The United Nations Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) made a monthly payment of R30 per exile in Africa. This was inadequate even for food needs. |